The Greatest Debate In Positioning, Abridged.

Should you really create a new category? Or just win an existing one? (Hint: it’s a false choice)

Is it really a good idea to create a new category?

Or is Category Design just an exciting fad that actually makes it harder to succeed?

This debate that has long raged among online communities of category designers and positioning experts has more recently spilled out into broad daylight, infiltrating publications such as

’s Newsletter, Harry Stebbings 20VC Podcast, ’s Product Growth and more.As a rare fan of nuance, I see validity in both arguments, but the tension between them - whether it should be this way or that way - is a false choice if you understand a concept that most people overlook.

Allow me to explain…

What’s the Beef and Why?

I’ve written much before about Category Design, and also compared Category Design to other contemporary positioning techniques. So I won’t rehash all that here.

Instead let’s jump to the most contentious debate between the two camps, which usually goes like this:

"Creating a New Category Is Too Hard and Expensive!"

This is the crux of the concern raised by thought leaders like

and .It’s not just that creating awareness for an entirely new category is expensive, it’s that when you attempt to remove yourself from an existing category, you also step out of the river of inbound demand from customers who are looking for solutions in that category.

So now you don’t just need to create category awareness from nothing, you need to create purchase demand from nothing. In other words, it’s immediately harder to sell stuff.

That is a valid and serious concern.

"No. Competing in an Existing Category Is More Expensive!"

A common response from Category Design evangelists like

is typically something like“Oh yeah? Expensive compared to what? Eternal hand-to-hand combat for market share and never-ending price comparison?”That struggle to compete for market share in the wrong category is what drives many business leaders to explore Category Design. They seek to escape the profit-eroding battle of price comparisons. Instead, Category Design offers the chance to expand the entire market, rather than simply vying for a slice of an existing one.

Given that our resources and career opportunities are finite, Category Designers believe it is ultimately more expensive to burn effort on competing in the “Red Ocean” of an existing category, whereas escaping to a “Blue Ocean” of a new category ends up being more effective overall.

The Inconvenient Truth

As you can tell from the resources I invest in writing about Category Design, I’m a super fan and tend towards the latter argument.

But at the same time, I know from experience that that passing up existing category demand in favor of long-term category creation doesn’t put food on the table right now.

It simply is expensive to create a category, it does take more time, and missing those easy-to-win, inbound customers in your early days is extremely painful.

So it really depends on the time horizon you are asking the question of.

Category Design aims to create bigger, more profitable outcomes in the future, but it is harder and more expensive in the short term. In my opinion, this is why articles are written claiming that practicing Category Design is like operating on “hard mode.” The immediate cost of losing inbound category demand in order to build for a future you may not survive to see feels like a losing strategy to many.

But what if there was a third approach that provided the differentiation of category design, with the short-term gains of existing category inbound?

What if it were possible to put food on the table today, while also sewing seeds for a much larger harvest in the future?

Well, there is. But most people miss it.

So let me attempt to connect the dots between an existing category design strategy and this problem, and build upon it with a new concept I call a “Bridge Category.”

Building Dams and Bridges

My idea of a Bridge Category stands on the shoulders of

and the strategic concept they call “Dam The Demand.”I don’t believe this was in the original Play Bigger book that popularized category design, which could be why so many people miss the concept.

It’s about interrupting customers when they are shopping, and then educating them on the advantages of heading in a new and different direction. (“You think you want that, but you really need this!)

(In which “this” and “that” are entire categories of products, not just a pivot from one brand to another).

I like to picture that there is a river of demand flowing toward an existing category, so you build a dam and reroute the demand to your new category.

As one aspect of Damming the Demand, The Category Pirates recommend modifying the existing category name with a “differentiating word” in front such as:

It’s not a car. It’s an electric car.

It’s not a watch. It’s a smart watch.

It’s not a computer.

It’s a personal computer.

It’s not a book. It’s an eBook.

It’s not software. It’s cloud software

It’s not a desk. It’s a treadmill desk.

Paired with other appropriate growth strategies, this would allow the eBook company, for example, to easily catch existing inbound demand for (print) books, for example, rather than trying to create category demand from scratch.

So by employing this strategy, you can achieve both the radical differentiation you want from Category Design, and still feast on the inbound demand for the existing category.

Yum yum.

But wait, there’s more.

The Dam Can Also Be A Bridge

Let’s say your category vision is for something truly novel and exponentially different to the existing market paradigm.

Coming out of the gates with radically unexpected positioning and category name will not only destroy all inbound demand, it could also confuse the hell out of anyone you try to explain it to.

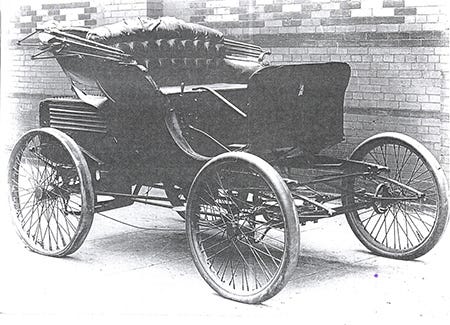

It would be like suddenly trying to create demand for a “car” when people have only heard of horses and carriages.

What the hell is a car?

But of course, there was a time when cars were not known as cars, they were known (at least colloquially) as “Horseless Carriages.” Carriage is the known, Horseless is the novel. In time, the horseless carriage category became sufficiently well known to survive without the “Horseless” and “Carriage” can be shortened to “Car.”

(Just as an aside, I often wonder if we are in a similar stage right now. If a car has an electric motor instead of an internal combustion engine, and if it drives itself instead of being driven, is it still a “car?” Right now the industry calls them “Autonomous Vehicles” but the folks on the street call them “Driverless cars.” What will we call them in the future? I don’t think we know yet.”)

Anyway, the point is, that a modified category name like horseless carriage does not need to be the final destination for the category, it can be a bridge that the market crosses en-route to the “Novel category” destination.

Existing Category: Horse & Carriage

Bridge Category: Horseless Carriage

Novel Category: Car

Feature Bridges and POV Bridges

The example of horseless carriage and most of the examples listed by Category Pirates in the quote above are quite functional and focus on the novel innovation or feature that has been added to the existing category.

“Treadmill Desk”

Bridge Categories are a little different.

They remain attached to the existing category, but the modifier is less of a function of the product and more of a teaser of the brand’s point-of-view.

“Cloud Software”

In doing so, they begin to prime the market for a different POV, while remaining in touch with the current reality.

A Bridge Category name creates a bridge from an established market to a novel category by modifying the existing category in a way that primes the market for an entirely new future category

Example: Figma

Consider the case of Figma and their “Collaborative Design” platform/product.

Less than a decade ago, most interface designers used Adobe’s Illustrator or InDesign tools for designing websites or apps, even though Adobe’s tools were originally intended for print design.

Then Sketch emerged as dedicated Interface Design tool, and ate a huge chunk of Adobe’s lunch. Sketch modified the category in a functional way and matched it with a streamlined feature-set targeted just at the needs of interface designers.

But it wasn’t long before another interface graphic design tool ate Sketch’s lunch by targeting the same use case, with a different POV.

Though targeted at the same audience and use case of interface design, Figma differentiated by telling the world their POV that interface design is a collaborative team process, not just the work of an individual designer.

Their “Collaborative Design” platform is a modified category, but notice how the modifier is more based on a virtue of the product, than a function or feature. Though the features of the product are very similar and aimed at the same user and use case, Figma’s category design forces design teams to make a choice - do you believe design is collaborative, or not?

That’s damn good category design. (And it looks like Sketch are now trying to compete at Figma’s game.)

Reaching Your Novel Category

Say you’ve established a bridge category and used it to differentiate from the existing category and establish demand for your POV.

You’ve dammed and harvested enough demand to grow through early adopter phases and have been educating and priming the market for your POV as you go. You’ve raised a Series A or more, have several million in ARR, and are ready to exit the chasm and activate the early majority.

Newly equipped with resources they didn’t have in the early days, many companies revisit messaging at this time and execute a launch into the new market segments. So this is a great opportunity to revisit the bridge category.

At this point, you have the option (but by no means the obligation) to move beyond the bridge category name and into something more novel by further severing the connection to the old category.

The Horseless Carriage becomes a Car

Cloud Software can become Cloudware

Collaborative Software could become Collabware*

*Note: I just made up that name on the spot, and I know it sucks. But my point is that if Figma decided to do something like that in the future, it could believably work after their bridge category, in a way that would not have worked without it.

Want To Try A Bridge Category For Your Start-up or Scale-up?

The process to discover a Bridge Category name is similar to creating a Novel Category name.

As I explained in Introducing Lean Category Design, there is a logical flow that guides you towards your right category name. Follow this, but seek to connect the POV to the existing category in a way that sounds natural and can believably catch on.

I’m writing about methods of forming POVs that lead to category names in a new article coming soon to this publication. Subscribe now to ensure you receive it.

Key Takeaways

The choice between “create” or “compete” is something of a false choice.

You can achieve radical differentiation AND harvest existing category demand by “Damming the Demand” from the existing category. Credit to

for that model.A Bridge Category builds upon the Dam the Demand strategy but modifies the existing category with a taste of the category POV, rather than a functional benefit

This approach primes the market for the new category idea while still harvesting existing category demand in the early, pre-chasm phase

You have the option to develop beyond the bridge category to an entirely new, novel category in your post-chasm phase, once you have more resources and the market is already partially primed by your bridge category

How Can I Help?

My mission is to create the future of your business by creating the future of your market.

There are 5 ways I can help you do this:

Your next CMO/SVP Marketing I am always open to meeting real innovators that seek a marketing leader that can bend the market to their vision. DM me on LinkedIn or book a chat at your convenince

Lean Category Design Coaching Get rapid resolution for your category design dilemmas and a testable prototype of your category strategy in just 2-3 weeks. Learn more here

FREE Lean Category Design course I will soon be offering a free email course to walk you through trying Lean Category Design on your own. It won’t be free forever, so signup now.

FREE Free Office Hours My office hours slots are open to anyone who wants to dump their category conundrums on me and pick my brain for 30 minutes. Totally free and no obligation - click here to book.

FREE Traction Design Substack If you found this post valuable, be sure to subscribe for many more articles of original thoughts and non-obvious insights regarding Category Design coming soon.

It makes sense for sure and I think a bridge category is a fine idea

In practice, I fear that it can be perceived as costing 2x in the minds of some stakeholders.

It’s the damned people that are not truly bought into category design that can force the org into a “stuck” position

In the case of Category design it is the destination, not the journey. In this journey, there be beasties in there.

Is it too expensive to execute Category Design?

My thoughts are, if there is a "river" of demand in the existing category, then one might question why one would need to do anything at all. Change for change sake may not make sense.

The very concept of category design, to me, seems appropriate in these situations:

- startup

- stagnation

- decline

A "trickle" of demand may mean something else entirely, like a future fail, and that might compel a push to category design.

It can be expensive to create a category and attempt to steer the ship in the new direction. Frankly, the inertia could be too great to overcome.

It might be easier and less expensive to create a category under a new brand to alleviate the weight of the old category.

One thing I have observed to be an immutable truth...

"Everything has a life"

Every company must continue to innovate, invent, re-invent, invest, and reinvest.

If they do nothing, they will eventually see that end of life looming on the horizon.

So, is category expensive? Perhaps.

But, is it more expensive to do nothing? Not likely.

A Bridge Category is a fine idea, as long as the organization does not become stuck.

Getting stuck is a real and omni-present danger.