The Invisible Intersection of Category Design and Lean Startup

How to Fail Small And Win Big With These Two Legendary Techniques

In the unlikely event I ever earn the privilege of being interviewed by Tim Ferriss, I already know my answer to his favourite question: “What is the book you have gifted the most?”

Though for me, it is actually 2 books: The Lean Startup by Eric Ries and Play Bigger, the original book on Category Design by Christopher

, Dave Peterson, Al Ramadan and .I’ve gifted them to my team members, made them required reading for suppliers that wanted to work with me and read and re-read them many times over. I’ve received immeasurable value from each of them, but even more from using both of them together, as complementary methodologies.

Given the value I see in the overlap, I’m always surprised that the opportunity to use the two together seems invisible to everyone else.

As far as I can recall, I’ve never seen an article exploring the synergies, though I have seen a few posts from the two camps slinging mud at each other.

Having practiced both methodologies for 8 years or more, I've explored various ways to use them together. This synergy forms the foundation of the Traction Design methodology.

A Quick Primer on Category Design

I first discovered Category Design in early 2016 when I listened to a recording of a Stanford lecture by Venture Capitalist Mike Maples Jr called “Dare to Do Legendary Things”

I distinctly recall the moment I was when he introduced this new theory of Category Design. I was driving on the 101 through Marin and it hit me like one of those insights that had been on the tip of my tongue for years, yet I had been unable to articulate it.

Here’s How I Explain Category Design For Newbies

People think in categories.

If I were to ask you:

“Hey, have you seen that new Audi QS?”

you might reply:

“No. What is it? An SUV or a Sedan or what?”

By doing so, you’d be trying to understand the category in order to understand the product.

That’s because putting products into mental categories helps people contextualize and understand them. This means that if you don’t actively tell someone what category your product is in, they will put you in a category of their own choosing.

The problem with that is that every category has one dominant leader (what the Play Bigger authors referred to as the “Category King”) that takes the vast majority (76%, apparently) of the profits from that category. So if you’re not already the dominant leader, you’re fighting every other player for a share of the remaining 24%.

Enter Category Design as a method for deliberately framing and naming an entirely new market category based on your unique POV on the problems your customers face. Then rather than merely advertising your product, you evangelize the problem and how that commands the need for an entirely new category of solution.

And just like when you find a doctor that “finally gets” your problem, your audience decides that since you are right about the problem, you must also be right about the solution. So as they migrate to the new category you define, they also find their way to your solution.

My All Time Favourite Example of Category Design: Dyson.

Up until the mid 90’s, the global market of consumers that wanted a vacuum cleaner without a bag was precisely zero.

The vacuum cleaner market was mature and entrenched, competing on established features such as motor power, retractable cords and aesthetics. It even had an eponymous brand “Hoover” as leader. (When I was a kid, everyone referred to “Hoovering the carpet.”). Who could imagine a more impenetrable market?

But then British inventor James Dyson came along and said basically said “listen, it’s not the motor, or the cord, or the looks that matters. It’s the bag.”

He didn’t need to name any individual competitors. Instead he wrapped them all up in one “anti category” of bagged vacuum cleaners. He didn’t need to engage in any feature based comparisons such as motor, suction or cords. Because his invention wasn’t just better, it was radically different.

Every early Dyson ad was less about the features of his product, and more about about the evil of all other vacuums with bags.

Bags are the reason you lose suction.

You get messy when you change the bag

Don’t you hate having to go back to the store to buy new bags?

His product looked strikingly different, but not just for style, it was deliberately to draw attention to the bagless POV executed as his “Cyclone” technology, allowing owners to see their dirt whizzing around inside.

He bisected the entire market into just two categories

Bagless vacuums 👍

Vacuums with bags 🤮

Consumers could suddenly see the problem with bags they had blindly accepted for decades, and newly enlightened, there was only one guy to buy from.

Within a few years, every vacuum brand was a cheap imitation of Dyson, fighting for a share of his spoils.

That’s just a quick summary of Category Design, but if you want to learn more, checkout

here on Substack, or check out me interviewing Christopher Lochhead himself in 2019 when I was host of the official Lean Startup Podcast.Why I Still Love Lean Startup

My affinity for The Lean Startup was just as immediate as it was for Category Design, but not because I had been instinctively doing it already, it was because I had been doing the exact opposite and had learnt through painful failure that it was the wrong way.

My friend Sam Hatoum told me about The Lean Startup in 2012 when we were in the middle of an 18 month long hell project that I was leading. It resonated so deeply I immediately immersed myself into the Lean Startup scene in San Francisco, volunteering at Lean Startup meetups and voraciously consuming the work of other authors like David Bland,

and many more.Though I still value and use Lean Startup today, it certainly feels the movement has lost momentum and has become more of a whipping boy than a poster child. It currently seems fashionable to publish articles that proclaim that “Lean Startup is dead” or blame Lean Startup for the failures of startups in that cohort.

In my experience there are 3 types of articles that attempt to dunk on Lean Startup:

Articles written by people that didn’t really understand or even read it

People just creating click bait for their own visibility

Valid arguments and criticisms, but that were beyond the original scope of the book

Although the first two topics don’t deserve being linked to, it's worth exploring areas that The Lean Startup did not cover and how it can be supplemented with other methodologies. This includes seemingly unrelated ones, such as Category Design.

Clash of Methodologies

As far as I am aware, this is the first article ever to explore the synergies between Lean Startup and Category Design.

But there is certainly some precedent for opposition between the two camps, and even a little mud slinging.

The delightfully outspoken Christopher Lochhead himself has gleefully teased Lean Startup concepts such as MVP or Product-Market Fit.

Though with respect to the great Mr Lochhead, I think his criticisms of these are more reactions to the nomenclature used than the underlying concepts themselves.

Quick aside: In a recent interview on Lenny’s podcast with

, Eric Ries addressed the criticism of the term “Minimum Viable Product” and accepted the need for a new, better name.While I’ve seen many folks suggest terms like “Minimum Delightful Product” I think the solution is to call it a Minimum Viable Prototype, not product.

In my experience, the common objection to MVP is based on misunderstanding it to mean that a stripped back, crappy version of a product should be enough. But that’s not the intent at all.

The true intent of MVP is to get valid feedback on a hypothesis as soon as possible. And the MVP itself is whatever is the quickest, simplest way possible to run a fair test. It could be just a user interview!

Nobody is saying that entrepreneurs should launch crappy products as real products. That’s why Minimum Viable Prototype is a better term, because it distinguishes the throwaway test artifact from the real customer one.

There. I solved it for you!

As far as I know Eric Ries and the Lean Startup community have never publicly commented on Category Design (other than to allow me to interview Lochhead on their podcast!).

However I did often notice a certain revulsion from some of the more extreme Lean Startup zealots in the community to any methodologies that leaned more towards opinion and away from testing and iteration.

At first glance, it seems that the empirical approach of Lean Startup is the direct opposite of the opinionated Category Design approach, but in fact this is exactly where the intersection hides.

3 Principles To Align and Complement Lean Startup and Category Design

Through my practice of both methodologies over the last 8 years, I’ve found these two camps are actually ideologically aligned on the following 3 principles:

1. Research the Current State, Not the Future State

If there is one quote that Lean Startup practitioners hate having thrown at them, it is this:

“If I had asked my customers what they wanted, they would have said faster horses!”

–Henry Ford (Allegedly)

Many people misinterpret this quote as Ford saying that he knows better than customers and doesn’t need to ask. They then throw this quote at Lean Startup practitioners as evidence of why entrepreneurs should not research and test with customers.

But that’s not the only way of reading this quote.

Here Is How a Lean Startup Practitioner Hears The Faster Horses Quote

A Lean Startup practitioner would never have asked the customer if they wanted a car or a horse in the first place.

They would have asked careful questions to see how satisfied they were with the speed offered by available horses, and would have considered hearing this feedback to be excellent validation of their problem hypothesis.

Hypothesis: We believe that people want to travel faster than is possible with horses, and would welcome a new type of transport that enabled this.

Result: Validated

Here’s How Category Designers Hear That Quote

A Category Designer would viscerally feel the problem of slow horses, but “reject the premise” of a horse as the only way to go faster.

They would consider all horses of any speed to be the old way of doing things, and envisage a new category of horseless carriage as the only acceptable future.

Crucially, They would not expect customers to be able to see or understand this new category until they had created it and evangelized it. They would consider it their job to move the market’s perception from the old way of faster horses, to a new way of something that is not a horse at all.

The Alignment Between Camps

Step back and look, and we can see that both camps align on not asking the customer’s opinion on something that they could not yet conceive.

In both cases, we use customer research to understand the true state of the old world that precedes our innovation, but it is our job, not the customer’s job, to conceive, name and frame the future that our innovation enables.

2. Win Big and Fail Small

Category Design is billed as a path to creating bigger, more valuable outcomes, as is reflected in the name of the original book: Play Bigger.

Many people might consider this to be in opposition to Lean Startup, which has been accused of creating startups that are unambitious, incremental and lacking in vision.

Again this is a major misunderstanding of Lean Startup.

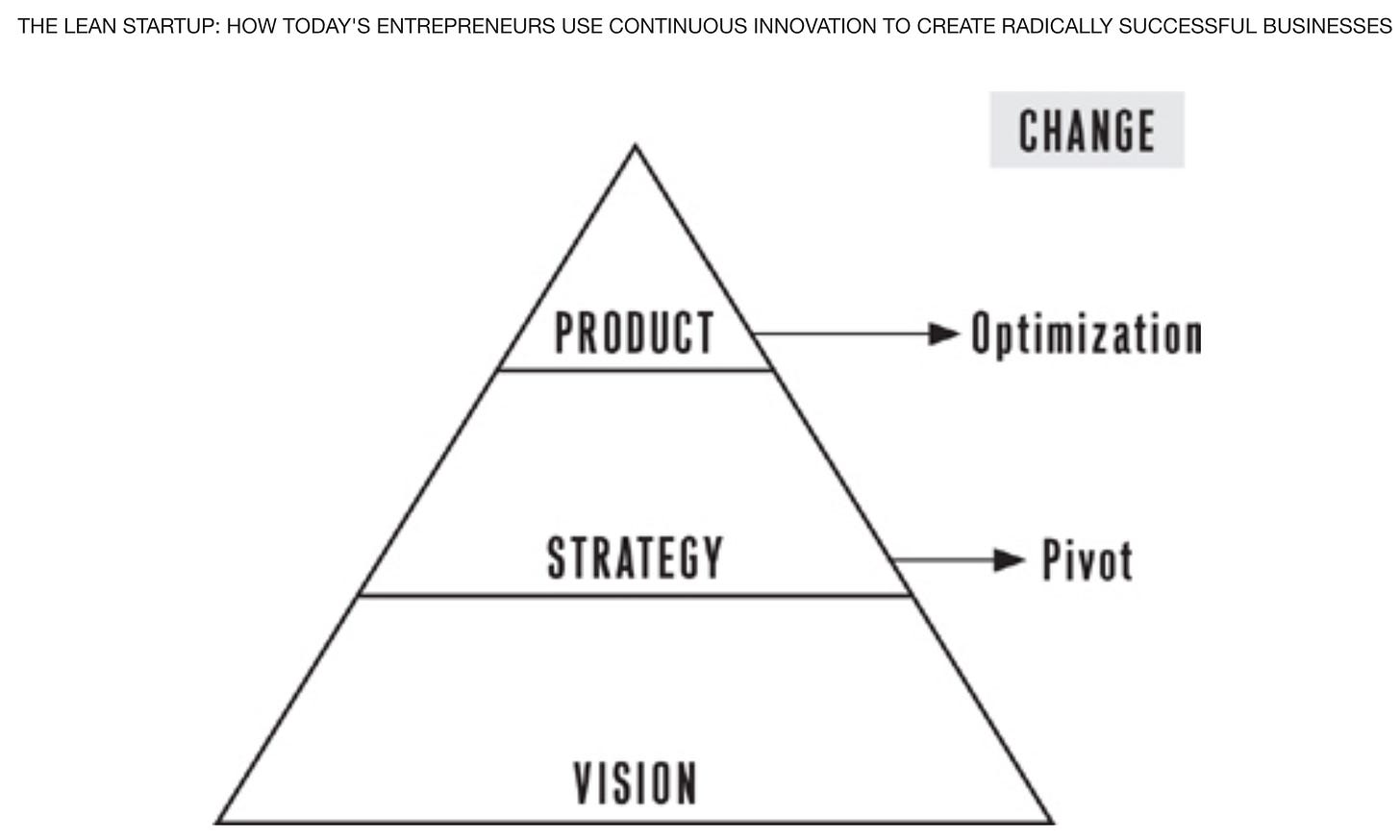

If you don’t believe me, read it again. For a start you’ll find that chapter 1 of the book is actually titled “Vision” and talks about the importance of having a north star vision that you iterate towards and separates the concepts of Vision from the entities of the strategy and the product.

As the diagram illustrates, the optimizations and pivots recommended by the lean startup approach are applied at the level of the product and strategy, NOT at the vision. Neither Ries nor the other Lean Startup thought leaders recommend that you start a startup without a vision, or change the vision haphazardly as you go.

https://twitter.com/ericries/status/221318901018017792?lang=en

Maybe some entrepreneurs did misread or misinterpret Eric’s advice and enter the startup journey just randomly testing various hypotheses without an overarching vision of what they were trying to achieve.

But that’s not, and never was what Lean Startup was about.

The important question to ask yourself it this:

If you’re going to win, would you rather win small? Or win big?

Of course you’d rather win big

But if you’re going to fail, would you rather fail big? Or fail small.

Of course you’d rather fail small.

This is the second alignment

As an entrepreneur, you want to fail small so that you can win big.

Category design is a path to creating a bigger future for your innovation.

Lean Startup offers a method for failing small.

3. Compassion for the Entrepreneur

The benevolent virtue that both Lean Startup and Category Design share is their concern for the fortunes of the entrepreneur.

What Ries taught the world with Lean Startup was that most of your assumptions about your startup are probably wrong, so you better discover where and why you are wrong as fast as possible and adpat (pivot) before you run out of runway and fail completely.

But failure is not binary, and spending a decade of your career on a mediocre startup that does not reach your ambitions is actually worse. Most people underestimate the pain of competing in a crowded market, which Category Design aims to provide a route out of.

Failing early seems painful, but a decade of unsatisfying mediocrity can be worse.

Be A Progressive, Not A Zealot

As a critical thinker I do enjoy challenging and debating the principles printed in texts like The Lean Startup and Category Design.

But I never expect any text to be 100% perfect without exception, and I certainly don’t expect that any book can cover unlimited scope. I’ve seen a surprising amount of rejection of these books for topics that were not, and should not have been included in the original texts.

Both books had a job to do, and did it well, but both movements are now far bigger than their original books.

The Lean Startup spawned global meetups, a summit conference and a number of great thinkers and writers that built upon the original work

For some great writers, Checkout

and on Substack and David Bland to name but a few

Play Bigger Author Christopher

now writes the awesome with Eddie Yoon on Substack, and there is a great new community called Category Thinkers created by Mike Damphouse, Pablo Gonzalez and

As valuable as I found the original books, I received the most value of all from the communities that followed them.

How to align Lean Startup and Category Design In Practice

In the future I plan to share many detailed techniques that I have developed to fuse the scientific method of Lean Startup with the artful and opinionated Category Design philosophy.

If you want to see these in detail, subscribe now for free

Want to Chat More?

Click that subscribe button and you’ll get an email containing a link for Substack subscriber office hours. You can also DM me via LinkedIn and Twitter.

Makes sense to me! It's been ages since I read Lean Startup so it was nice to get a refresher and remember how much of it still aligns with my thinking today. Still need to read Play Bigger :)