The Traction-Native Startup Way

And The Cure For Product-Market Fit Derangement Syndrome

The new methodology of Traction Design is founded on this deceptively simple insight:

If the job of a startup is to de-risk their riskiest assumptions as soon as possible,

and the greatest threat to startups today is traction,

then de-risking traction should be the first priority.

I say “deceptively” simple, because this is the exact opposite of how most startups operate, and changing that is hard.

Most startups operate a product-before-traction process, because this is what the industrial startup complex teaches them to do. 15 years ago, many founders needed to learn that. But we now operate in a different world.

At the heart of the issue is a tacit fanaticism for product-market fit - a powerful but misunderstood concept that is dangerously used beyond its original intent.

So if we want to rebuild the startup ecosystem for the modern age of AI, we need to start by burning down the temple of product-market fit.

This will be heresy to many, so let me explain why this is not crazy.

The First Priority of a Startup is to Mitigate its Deadliest Risks.

This is of course the primary message of The Lean Startup and Customer development movements, where Eric Ries, Steve Blank and others teach not just the importance of testing and learning, but of identifying the absolute riskiest “Leap Of Faith” assumptions and testing those first.

David Bland teaches a further “Assumption Mapping” technique to identify which assumptions are the most critical for your business, based on how much evidence you have to validate your assumption and how catastrophic the consequences if you are wrong.

This mindset is also advocated for by decision making expert Annie Duke. In her book Quit Annie tells the story of Astro Teller’s Monkeys and Pedestals philosophy that ingrains a “Do the hard work first” culture into Google’s X Moonshot factory.

So hopefully this should be fairly uncontroversial.

In the Age of AI, Your Deadliest Risk is Traction

Traction, not product is the battlefield on which startups die.

This is a harder point for some people to metabolize, because this has not always been the case. But AI and other forces have ushered in a new age of innovation that changes everything.

The Three Ages of Innovation

The culture of experimentation for generations of inventors and entrepreneurs has evolved like three waves of a trilogy, which I map to David Bland’s three macro assumptions:

Act One: The Age of Feasibility

In the days before the cloud, before open source software libraries - or even before software itself, it was certainly true that the greatest threat to an inventor’s idea was feasibility.

“Can I Build This?”

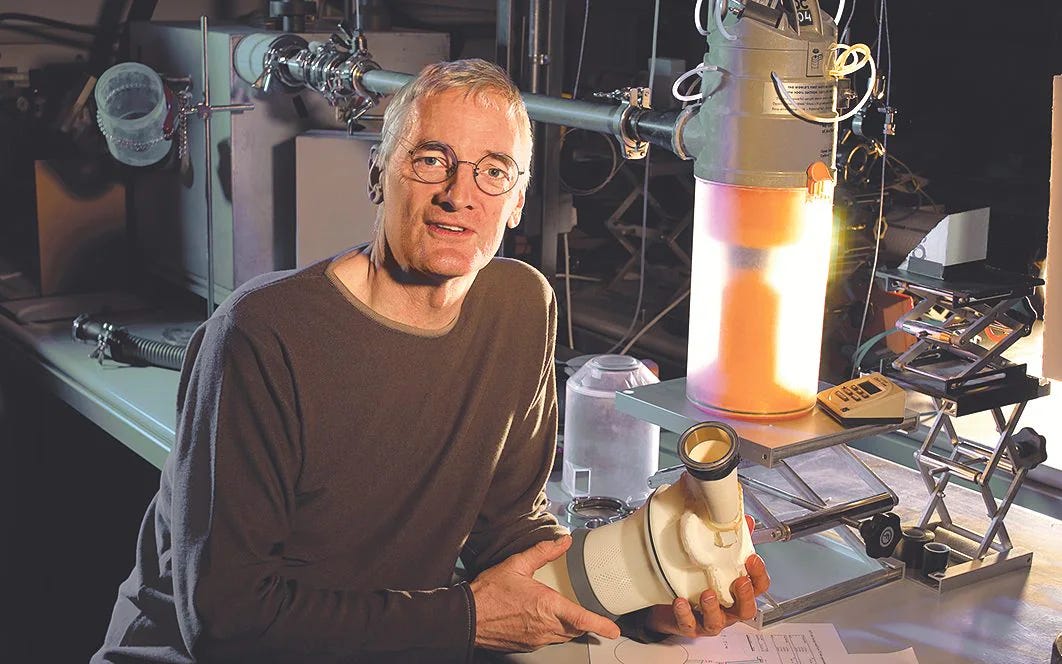

The stories of inventors like James Dyson toiling for years through hundreds of prototypes are as legendary now as they were necessary then. In those days, it was totally appropriate to focus first on whether you could build something that really worked before worrying about much else.

But as software ate the world, and production became commoditized, feasibility risk receded. More products become possible, which means more products become available.

This moves the goalposts of concern to a different field: Desirability.

Act Two: The Age of Desirability

By 2010, Steve Blank, Eric Ries and others had noticed that feasibility was no longer the primary determinant of success.

What the Lean/customer discovery leaders taught was that any aspect of your assumed business model is likely wrong, and so every aspect should be treated as a hypothesis and approached with a scientific method of experimentation.

In my experience, while keen students of these practices got the memo about experimentation across the whole business, the wider world that heard of MVPs, Pivots and such concepts second hand mostly just applied it to product desirability.

We can build it, but does anyone want it?

The major “aha” for most people was the understanding that their assumptions of what the customer wants are probably wrong, so they should find out why and adapt.

Though simple, this was a complete mind-fuck for most people. Just look at the cult popularity of Y Combinator’s “Make something people want.” Though it sounds screamingly obvious, if it were, PG wouldn’t have needed to say it.

And there certainly wouldn’t need to be TShirts and posters dedicated to it.

Act Three: The Age of Marketability

The third of David Bland’s domains is viability.

This says OK, you can build it, and people might want it, but does it make for a good business?

I’ll go a step deeper within viability to highlight marketability, specifically.

You can build it, people want it, but can you reach them and convert them into customers profitability?

Clearly if you can’t, you don’t have a business at all. But this is precisely the existential threat for startups today, thanks to a radical shift in context from three major forces:

The Startup Funding Crunch

The US VC funding activity in January 2024 saw a year-over-year (YoY) decline in deal volume and value by 61.2% and 37% respectively compared to January 2023. With funding now harder to unlock, investors are able to demand greater market traction from startups to de-risk their investmentA firehose of great products

Even prior to widespread availability of AI, the abundance of SaaS, OSS and ubiquitous understanding of desirability testing meant that it had never been easier to create not just a working product, but a great product. In any given category, there have never been more great products available.PoweredTurbo-charged by AI

The emergence of generative AI pours fuel on the fire of point 2. From products like FForward that assist customer research to virtual developers like Devin to build products to marketing assistants like Dreamwriter to help market it. Designing, building and launching a great product is now even easier, which in turn means there are even more of them.

All of this creates an over-abundance of supply that is growing far faster than the available demand. And while it is true that some products create net new budgets, most don’t.

So short of an explosion in spare cash to burn, it is inevitable that we will see a pile up of great products, jammed by constrained demand.

Don’t Save The Worst For Last

In the age of AI, winning traction in the market is what makes or breaks your start up, so it makes sense to address it first.

This runs counter to the intuitions of most people that think “the best product wins” and is a potential blind spot for most founders that typically found a startup following a product or technology insight.

The problem is that building a product and validating with real customers that it really solves their problem can take anywhere from 3 to 18 months, and reaching product-market fit takes even longer. Not only does this leave you little or no time to validate customer traction, it compounds the problem. It is quite possible that you can build a complete product that customers love but still fail to achieve scalable traction because:

The market for it is too small, too hard to activate or too competitive

You find a signal from a different market that values the problem more, but they require different features or distribution channels

Or worse

Uncovering such issues when you’re already 80% of the way through your runway is not only deadly for your startup, it can be disastrous for you personally, having lost time, money and career opportunities that could have been saved if discovered earlier.

Faced with this, your opportunity is to flip your order of focus and validate traction - or potential traction - before burning your entire runway on a feasibility and desirability testing a product that does not have the potential for traction.

To unlock that change, we first need to slaughter a sacred cow of startup process: product-market fit

Product-Market Fit Derangement Syndrome

At the heart of the product-first mindset is the directive to focus exclusively on product-market fit, as was preached:

"The life of any startup can be divided into two parts — before product-market fit and after product-market fit. When you are BPMF, focus obsessively on getting to product-market fit. Do whatever you need to do to get to product-market fit."

This is of course from Marc Andreesen’s infamous article that popularized Andy Rachleff’s concept of product-market fit.

Let’s introduce Rachleff’s Corollary of Startup Success:

The only thing that matters is getting to product/market fit.

I Used to Love Product-Market Fit

Only a true dork could claim to love a concept like this, but I am that dork, and this is true.

Since first discovering the concept in about 2015, I have read and written multiple articles, white papers, delivered presentations and even once started a consulting practice dedicated to product-market fit.

On reflection, the reason I became so enamored with product-market fit, is that it feels so powerful to conceive of a certain tipping point in the life of a startup where they do or don’t make it.

Before PMF you just have an idea. After PMF you have created a genuine new business.

This spoke to me as a fundamental first principle of business, one which was completely missing from the campaign-led agency world I’d left.

But it is not only me that’s obsessed. Product-Market Fit is an alluring and imperfect concept that left much scope for debate, creating a void for countless articles, podcasts, books, consultancies and more dedicated to operationalizing it.

But Now I Hate PMF

It recently dawned on me that I am obsessed with PMF not because it is so great, but because there is so much wrong with it.

There are many arguments against PMF, such as:

That it implies you have to bring the product to an existing market

That the idea is right, but the order is wrong - it should be market-product fit.

It is an illusion because it is fleeting, and as soon as you have found it, it changes.

These are all true, but they miss the bigger problem, which is that

Product-Market Fit is a powerful goal, but a terrible metric.

Consider the following points:

PMF is quantified only as something that “you know if you have it, or if you don’t”

Yet this extremely detailed and well researched article from Lenny Rachitsky tells how many very successful founders never felt they had PMF at all

There is widespread confusion of what it means, let alone how to measure or achieve it

Even top business thought leaders disagree about foundational issues such as whether product-market fit includes validating growth metrics, or if is just a product metric

I was even recently in a startup leadership meeting, where the CEO declared:

Our number 1 objective this year is to achieve PMF!

So…

what do we think that means?

He was literally telling the startup team that the most existentially important objective for the company was to achieve something that even he could not define, let alone measure if/when we achieved it.

(This is not a dig at that CEO, it’s just a great example of how PMF deranges even smart people.)

Let's Pause a Moment to Consider How Absurd This Is.

The startup ecosystem is telling you that the most important thing that you can possibly do before anything else, is something that cannot be defined or quantified.

That you will know if you have it, or if you don’t - despite the aforementioned evidence that this is not true.

Oh and by the way, you might feel and declare that you have it, but I might decide I don’t really feel it, and declare that you don’t.

Can you think of any other example in business where we place such emphasis and faith onto something so nebulous and undefined?

I can’t.

I’ll bet that everywhere else you look in business you hear things like “You can’t improve what you can’t measure!” and “Objectives should be S.M.A.R.T!”

This is the deranging effect of PMF.

It misleads you that your first priority is to optimize for something that is fundamentally impossible to optimize for.

To be absolutely clear, I’m not criticizing Andy Rachleff or Marc Andreessen for their discovery and evangelism of the idea. Having researched the origins I have respect and reverence for their powerful insight into the importance of a product and market satisfying each other.

The only shame is that Andreessen’s seminal post ended with:

Editorial note: this post obviously raises way more questions than it answers. […] All these topics will be discussed in future posts in this series.

Unfortunately, they were not.

The Bigger Problem Is Not PMF, It’s Product-First

What might surprise most people that consider PMF a product metric, is that Andreessen’s famous description of PMF was within an article called “The Only Thing That Matters” and that thing in question was the market, not the product.

Andreessen shares what he calls “Rachleff’s Law of Startup Success:”

The #1 company-killer is lack of market.

Andy puts it this way:

When a great team meets a lousy market, market wins.

When a lousy team meets a great market, market wins.

When a great team meets a great market, something special happens.

This is perhaps only more true now than then, and enforces my main argument: If the market is the most critical factor, then you should treat it as your first priority.

What you need is a new method of solving the market traction risks first, while you build your earliest product, or even before.

What If You Could Become Traction-Native?

What if you could validate that your product could get customer traction, right at the very start of your runway burn?

What if your months of crafting your product could be spent with the assurance that the product is already validated to have inherent traction potential?

What if you could weave traction into the very fabric of your company culture, like others might seek to be “digitally native” or “to have a culture of experimentation?”

You can do this.

It is easier and faster than achieving problem-solution fit or product-market fit. And both these concepts become more achievable if you solve traction first.

The unlock is to break the outcome of validated market traction into two steps:

Validation of the potential value (before you build)

Measurement of actual execution (after you build)

Like the physics of potential energy and kinetic energy.

Validate Potential Traction Before Building

Before committing to a market, you should be able to check that it holds enough potential energy to satisfy your own ambitions.

It should be possible to validate that

You have identified a real problem that is meaningful and valuable if solved

You have identified the right customer segment, and it is big enough, self-referencing and winnable

You know exactly who the customer is and how they perceive the problem

You know how to describe the outcome you will create for them, and validate that they love this proposition

You can position your product as radically different and immune from competition with other players

Your customers are willing to pay a good price that gives you a desirable margin

In a sense, we need a prior state of “Offer-Market Fit” that precedes Problem-Solution Fit and Product-Market Fit.

The only other person I’ve heard argue for something similar is Ash Maurya of Lean Foundry, and the creator of the Lean Canvas. In a recent article he wrote:

Validate your problem insights using an offer before building a solution. Building a solution takes effort.

A better and faster approach is testing your solution through a proxy.

Meet the offer.

Once you’ve discovered one or more problems worth solving, get the same people to first buy your “promise of better” packaged in an offer before building anything.

Think Demo-Sell-Build versus Build-Demo-Sell.

Ash Maurya - Lean Foundry

He also lays out a process for innovation that solves many of the issues that I’ve raised in this article, which I highly recommend.

I owe a lot of my experience and ideas to having studied Ash’s work, so it is with a humble respect that I propose Traction Design as a method that adapts & augments the offer-first approach in a couple of important ways

Adding Positioning and Category Design as deliberate parts of the process, which I’ve not seen addressed in Ash’s models.

Starting afresh with new, simpler names for the key stage gates

The New Milestones for Traction-Native Entrepreneurship

As Different by Christopher Lochhead 🏴☠️ says, “We can't use old language to communicate new things” and this is especially true when it comes to deranging old concepts like Product-Market Fit.

We therefore need to start over with new, measurable, tangible milestones:

Customer Traction

Proving that your offering has the potential to earn traction with a truly valuable group of customers (AKA offer-market fit)Product Traction

Proving that your product really does solve the problem and delight the customer (FKA problem-solution fit)Market Traction

Proving that you can reach your customers in a scalable and profitable way and grow sustainably - thereby satisfying both the market and yourself (IMO true product-market fit)

Each of these steps should have logical and objective metrics to quantify them. I will build these out in a future post.

For now, just know this:

In the age of AI, Traction is your first priority.

So make traction your first action.

Join This Publication as Traction Design is Built in Public

The Age Of Desirability encouraged more entrepreneurs to “get out of the building” sooner and spend less time in stealth. Our current age of AI sees this trend accelerating further.

We now live in a #buildinpublic world where savvy entrepreneurs are building audiences for their product while (or even before) they build the product itself.

So rather than write Traction Design in secret and release it as a finished book, this Substack publication is where I #thinkinpublic about these concepts. I invite your feedback, and I really do mean that.

The mission of Traction Design is to create the methodology to stop your startup dying on the battlefield of traction. And the role of this publication is to craft that methodology collaboratively.

So if you agree that solving traction is the first priority, and you believe that it is possible, join me.

Subscribe for free and comment with your thoughts and feedback.

This is really helpful. I've been wrestling with undestanding and communicating Product-Solution fit vs. Product-Market fit for a while. I think your idea of Offer-Market Fit is a big help.

I'd love to hear what you think about Minimum Viable Segments for the earliest stages.

Tell 'em Chris 👏🏴☠️